Why we weigh Ingredients

When you read recipes, you often find ingredient quantities like "a tablespoon" or "two cups". These descriptions are very common and sound great in theory. When you scoop out some peanut butter for a recipe, there is no extra step involved, you just stick your spoon in the butter, and put it out and work with it.

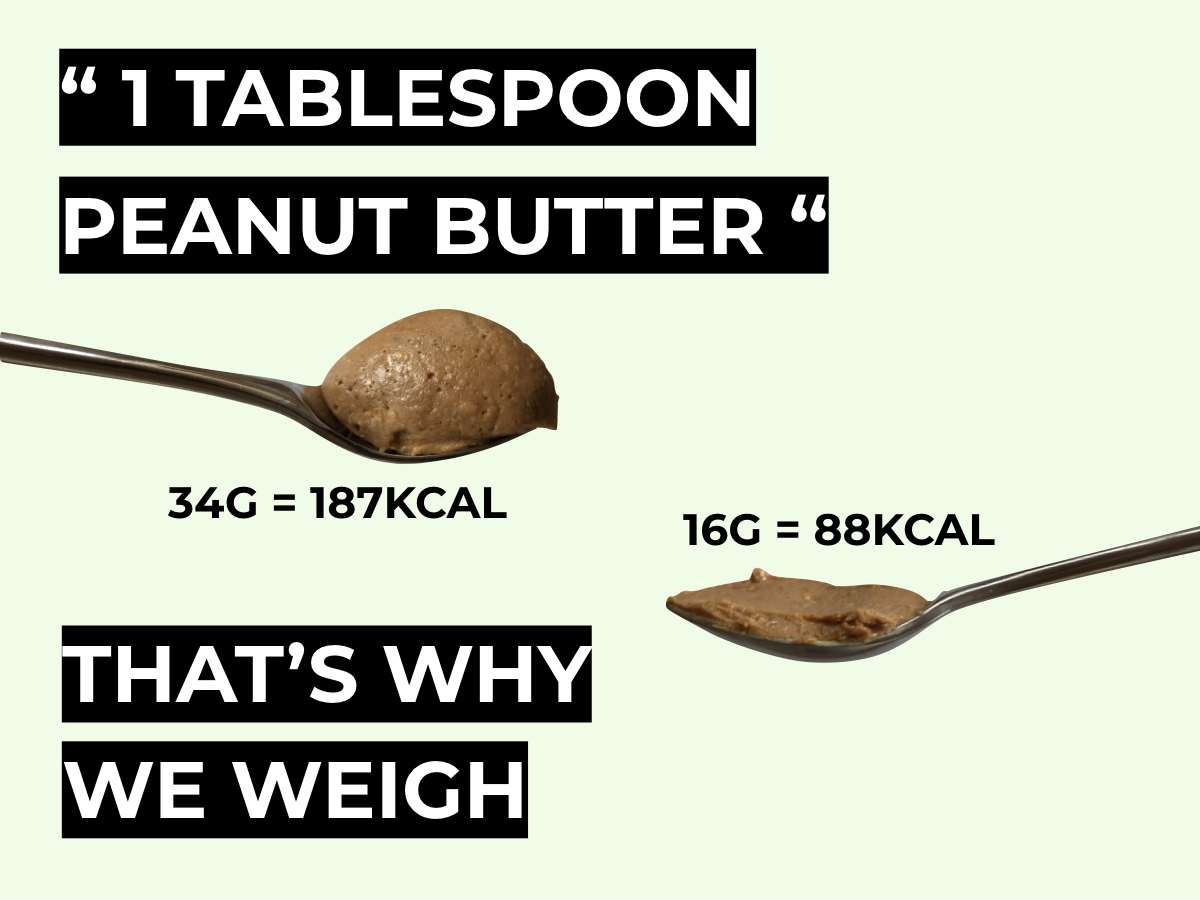

The problem with that is a pretty simple question: How much is a tablespoon?

Without going into the discussion of different tablespoon designs and sizes, just take the picture above: Both spoons can be said to be "a tablespoon of peanut butter". But one has 34 gram, and the other 16g. The larger one has 187 kcal, the smaller one 88 kcal.

So, which one is it?

There's a difference of over 100% between them, so the question is not nitpicking. While that's not a real problem with a single ingredient (100kcal up or down is a much smaller deal a lot of people would like you to believe), imagine doing this with all of your ingredients. With a variation of up to 100%, your total energy intake can vary wildly, and you wouldn't even notice it, because you are following the recipes.

That's why we recommend weighing all your ingredients, and that's also the reason why we state all ingredients of our recipes in weight. It's the only way to be precise about your intake.

But what about size-based guidelines?

You've probably come around guidelines that base recommended intake on body parts; like "1 palm of protein, 1 fist of vegetables, 1 cupped hand of carb, and a thumb of fat"

They are very good in a pinch, when on the road, or when you don't have a kitchen scale (or don't want to look like a type A person). But they basically have the same problem as customary units ("1 tablespoon"). They introduce a rather big margin of error that can be easily avoided by weighing your ingredients.

An alternative approach to guestimating quantities

If you can't follow a recipe, or can't measure a lot of ingredients sufficiently, Nutrfy always offers the option to "freestyle" a meal. In that case, you get a recommendation for the quantities of a carbohydrate source, a protein source, a fat source and a recommendation for the amount of greens to add.

This works very well with packaged foods.

Let's see how this works out in practice:

Assume this is your freestyle recommendation for a meal:

133g is roughly 1/4 of a pack of spaghetti, so that's easy. (Technically, it's 125g, but when you freestyle, it's not the time to split hairs).

A good protein source would be chicken, and if you buy chicken filet, the weight is printed on the package. Typically, it's around 200g, so if we use 1/5 of the chicken, we have 40g of protein.

When it comes to veggies, just use as much as you like, and as much as possible. With very rare exceptions, veggies are not very calorie-dense, and eating too much wouldn't actually make a difference.

And finally, the 20g fat are a dash of olive oil to fry the chicken, and a little bit to put over the spaghetti.

Violá, that's it. You just eyeballed your first freestyle meal.

Yes, it's not perfect, and yes, it's not the most incredible dish ever cooked up, but it's ok, and you hit your macronutrient targets without any hassle.